The Saints

The contemporary icons of Nikos Kypraios

Greek Artist Nikos Kypraios Reinterprets Byzantine Art

SINGAPORE — Byzantine art, with its flat, serene Christian icons, is re-visited in new exhibition by a Greek artist Nikos Kypraios. The 69-year-old artist is putting on a solo show titled “Interiors of the Soul: The Byzantine Icons of Nikos Kypraios” at Sculpture Square, opening this Friday.

Some 20 artworks of saints including Saint John the Baptist, Saint George and Saint Michael will be on show. His oil-on-paper works are heavily influenced by the liturgical paintings of the Byzantine era in the Middle Ages, depicting religious figures. In contrast to the solemn and gilded images of the bygone era, Kypraios’ art is more freely expressive, with gestural brushstrokes and a deliberately faded and aged quality.

His works are priced between $4,500 to $8,500. Part of the proceeds will go towards Sculpture Square to fund its new visual arts programmes that support talent development and community engagement.

“Interiors of the Soul: The Byzantine Icons of Nikos Kypraios” is on at Sculpture Square from Feb 8 to 18.

Articles of faith

The 24 icons in Nikos Kypraios' show evoke familiar Byzantine works, yet convey a sad but human connection lacking in traditional pieces.

By LENNIE BENNETT

Published December 22, 2005

TARPON SPRINGS - People sometimes speak of viewing art as a spiritual experience. Museums don't generally try to foster that response, providing instead a neutral arena where observers can bring in whatever predilections they choose.

The Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art has temporarily abandoned neutrality in its installation of contemporary icon paintings by Nikos Kypraios, a serene, contemplative respite from holiday frenzy. An arch balances atop two partitions, creating a churchlike entrance. The massive gray concrete wall of the museum's special exhibitions gallery, hung with portraits of saints, has become monastic in its austerity. Ancient Orthodox chants emanate from an unseen source. You expect incense at any moment.

It's an effective setting for Kypraios' reverential works, wrested from his Greek heritage and made new with expressive interpretation. The artist left his home in Greece in the 1960s, during a repressive political and military regime. He lived in Australia for about two decades, then returned home.

Kypraios is better known and admired for his luminous abstract landscapes, one of which is shown in a small adjacent gallery. The 24 icons were a special project, all painted in 1994, and all but two he has kept for himself. They work well as a collection. In the early years of both western and eastern Christianity, icons were powerful channels between the mortal and heavenly worlds, thought capable of delivering salvation, healing or divine retribution. Today, icons are still revered in the Eastern Orthodox church.

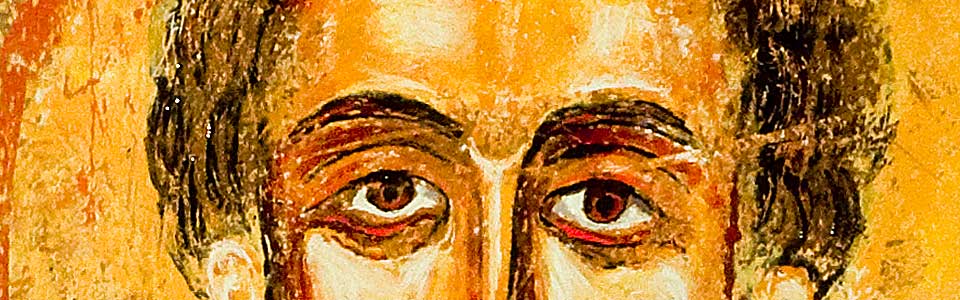

Though Kypraios' paintings are instantly recognizable as coming from the Byzantine tradition, they are nontraditional in intent and execution.

In their compositional focus, they pay tribute to the anonymous artists of the early church. The holy figures are flattened into color-field backgrounds and pose facing us, most of them staring with expressions that range from suffering to resignation. Saint Anthony, the hermit saint, has the sunken eyes of an ascetic; the archangel Michael gazes with the solemnity of responsibility. The Virgin Mary looks mournful as she tenderly holds a cherubic baby Jesus, anticipating a lifetime of loss. In another portrait, she stares at her empty hands in deeper sadness. Kypraios references conventional iconography without trying to replicate it, assimilating stylistic details of the past and infusing them with what critic Robert Morgan describes as "modernist expression, not about realism but about expressing the inner core of spirituality."

Despite their formality, all, even the nonhuman angel and Christ himself, have an individuality, a personality absent from traditional icons, which are given their identities by symbolic accessories or colors.

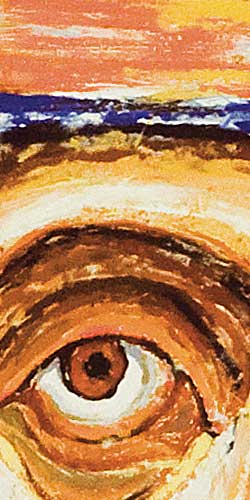

Kypraios' process also is thoroughly modern. Instead of the usual meticulous building of color on a smooth surface, he roughs up his canvases, scraping away layers or piling up emphatic swipes of paint. The viewer is reminded that, just as the subjects are not generic, neither is the artist. In that self-consciousness on the artist's part, the Great I Am of biblical creation shifts from God to the artist.

Some of the saints here are common to both eastern and western Christians, such as Saint Peter, a dignified elder with a surprising shock of blue hair. But Saint Fanourios? Wall text tells us his feast day, Aug. 27, has been celebrated for 500 years. No biography exists but he is thought to have endured multiple tortured martyrdoms.

Suffering, the Byzantine example implies, paves the road to eternal glory. In these contemporary versions suffering makes one more human.

And that tension is at the core of these icons. Kypraios has said they were not meant to be objects of veneration as "real" icons are. They seem to be more venerations of faith.

Icons of old kept their distance. Regardless of their lives on Earth, the martyrs, whatever horrors they had suffered on Earth, had attained a heavenly life of contemplative detachment. These for the most part look like people still in the middle of living. The best example of that tension is found in Christ Ruler of All, which depicts Jesus in one of the oldest iconic gestures known, raising his hand in benediction. As Kypraios paints this triumphant moment, Christ's eyes look questioning and his mouth is slightly open. Maybe he's about to say something, answer a question. Christ is responding, and response has always been a tenet of Christianity. But the tentativeness of this one says more about human longing than divine surety.

- Lennie Bennett can be reached at 727 893-8293 or [email protected]

REVIEW

"Nikos Kypraios: Icons" is at the Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art, 600 Klosterman Road on the Tarpon Springs campus of St. Petersburg College, through Jan. 8. Hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday with extended hours to 9 p.m. Thursday and 1 to 5 p.m. Sunday. Admission is adults $5, seniors $4, children and students free. The museum will be closed Christmas Day. 727 712-5762; www.spcollege.edu/museum

EPIPHANY: The exhibition was organized in response to Tarpon Springs' 2006 Patriarchal Epiphany Centennial Celebration. A weekend of activities is planned Jan. 5-7, and includes a liturgy celebrated by His All Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew at St. Nicholas Cathedral. For more information, go to www.epiphany100.com