The Furies and the Fate of Civilization:

Recent Paintings by Nikos Kypraios

Robert C. Morgan, Ph.D.

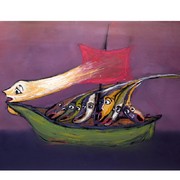

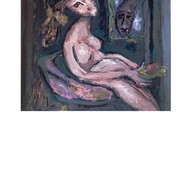

There is little doubt that the powerful images found in the paintings of Nikos Kypraios have a distinct reality all their own. As a painter, his subject matter varies from one series to another. At times, his work carries a contemplative, lyrical or poignant quality, while on other occasions, a surging violence appears, a metaphorical angst as if to repel the injustices he believes exist at the present. Whether Nikos paints the simulacra, or resemblances of iconic Greek portraits, or brutally scorched landscapes, or omnipresent mythic themes, he is fully committed to the act of painting. He retains the demeanor of a poet in all that he paints. He is capable of imagining the present in relation to the past, whether the past is centuries old or within a few decades. Reminiscent of Sartre, his sense of history is never removed from what he perceives and experiences in everyday life. He is alert and aware of the emotions that surround him. He never shuns the realities of his time, which through his paintings, become the time of the viewer. His instinct for seeing reality in his paintings verges on the prophetic. For Nikos, history always hovers within its own space and time, either moving forward or regressing towards the past. While he remains in touch with his memories, he continues to understand life as inextricably bound to art. In this sense, Nikos is a visionary artist who invents allegories that show us the truth of what is happening in the environment where we live and work. He is an artist with something to tell us, perhaps, to remind us, of what we are and who we are. His paintings project the idea of people living together rather than divided one from another. In essence, Nikos Kypraios is an artist intent on helping to improve the human condition of which we are all a part.

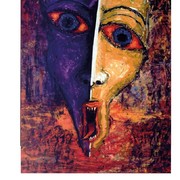

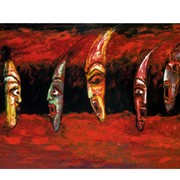

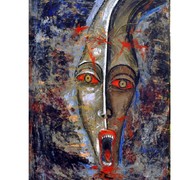

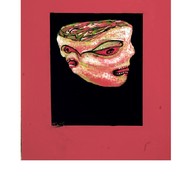

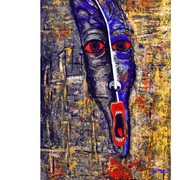

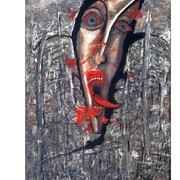

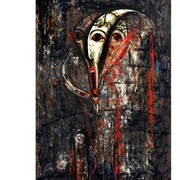

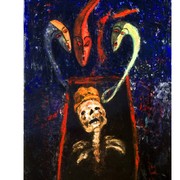

The current series of paintings focuses on the Erinyes [Furies], who lived primarily on Mount Olympus, but were known to frequently intervene among mortals due to some injustice they had performed, which required a just revenge or violent reconciliation. According to the artist, “Erinyes, were criminal spirits, revenging without mercy offenses committed against relatives and especially family murders…As Hesiodus described them, Erinyes were the daughters of the Earth, conceived from the Uranus blood, when he was castrated by his son Kronos. They were born from a crime that was committed from a son against his father… Erinyes were guardians of natural and ethical order. Every deviation from ethical legality brought exemplary punishment.” According to the poet Robert Graves: “[The Furies] were horrible, withered, savage, coal-black women with snakes for hair, faces like dogs, wings like bats, and burning eyes; they carried torches and cat-o’nine tail whips. The Furies often visited the earth, too, to punish living mortals who behaved cruelly to children, or rudely to old people and guests, or unkindly to beggars; and hounded to death anyone who treated his mother badly, however wicked she might have been.” This was, of course, the case with Orestes, who murdered his mother Clytemnestra to avenge his father, Agamemnon.

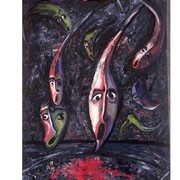

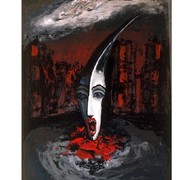

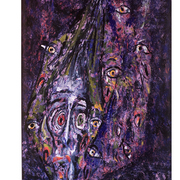

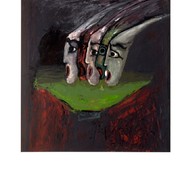

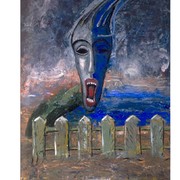

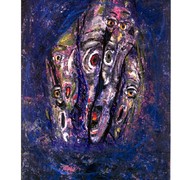

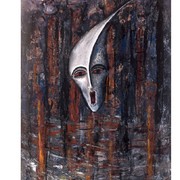

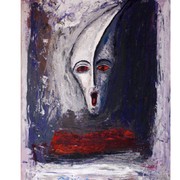

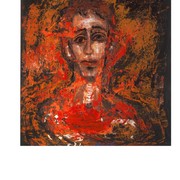

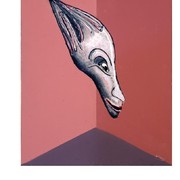

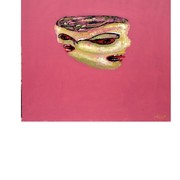

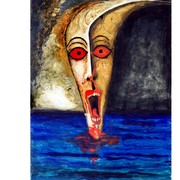

This recent series of paintings is based on the revenge of the Furies, not so much from the perspective of ancient Greece but from the point of view of the present. Kypraios has given us a sequence of paintings that constitute some of the most startling figures represented in his artistic career. Actually, they are not figures at all, which is one reason why they appear so startling. The Furies are heads removed from their bodies. As we examine the paintings closely, there is little doubt that the fierceness shown in these female heads are filled with relentless retaliation. They are not angels. Rather they mean to deliver an ill-fated omen on those earthly beings that have mistreated others and have brought untold misery and suffering into people’s lives. The Furies portray a form of dread that suggests haunting revenge, or a sudden unwanted visitation clearly meant for those who have furtively committed heinous crimes. The implication behind these Furies is that they are chasing perpetrators who have attempted to cover or disguise their true nature, to hide their real faces from the public-at-large. They engage in a kind of performance in order to present a mediated image of themselves, an image they believe people will see and believe. Their job is to unmask the perpetrators and bring them to justice, assuming they do not destroy themselves first in the process.

Once again, I and reminded of the philosopher Heidegger and his insight regarding the Greek tragedies once performed at the open-air theatre at the base of the Acropolis. His point was that these plays could only retain literary and historical value if future productions were translated into a present-day context. What I find exemplary about Kypraios’ paintings is the manner in which he has arrived at a similar viewpoint, equal to Heidegger’s hermeneutic vision found in the plays of Sophocles and Euripides. For Kypraios, the point is not to leave the Furies in the past, but to bring them back into the present and thus reveal a similar truth but within a new context, the historical perspective of the present. It is also worth noting the obvious. Kypraios is neither a philosopher nor a playwright. He is a painter and therefore works on a different level, a formal, pictorial level in which denotation and connotation are equally important. The Erinyes series both depict and interpret a point of view of the retaliation of misdeeds in the present. The dramatic unfolding occurs in one frame and one painting, not over a period of hours on stage. Even so, Kypraios gives us everything we need to know. One looks at the Furies with fear and trembling. Like the media of the present, they are the police who are delegated to punish those who commit crimes against innocent people at the mercy of those who engage in the corruption of power.

The genius of Kypraios is found in his ability to deliver content in his paintings in a vivid formal manner without promoting a point of view. In this sense, the Erinyes paintings are less overtly political than they are expressionist. Kypraios is a painter who paints according to the emotions he translates visually. The source is a romantic one that emanates from interior thoughts and feelings. To some degree he is an existentialist as much as a classicist. This makes his work all the more unique. At the same time, he is intuitively aware of the color, texture, shapes, marks, and compositional strategies as they come into his paintings. This is the sign of a true master. These formal aspects of his work are intuitive, not academic. For Kypraios there is no separation between form and content. They blend together. They become one, then separate again, always undulating back and forth. His paintings become celebrations of his magnificent intuition, a way of getting into the truth of what matters, without wasting time with incidental academic exercises.

The Erinyes series are some of the artist’s most forceful and explicative painting to date. They resonate with power, not just political power, but the truth of his emotions. The truth, as relative as it may appear, is what Nikos Kypraios wants to reveal through painting. Great painters are perpetually confronted with this issue. How to find the core belief of what one is doing? How to discover, or perhaps, rediscover, the power of what one is trying to achieve through a formal or expressionist means, through color, through line, through shape, through the figure, through the gesture. How does one make it happen sin a convincing manner? For Kapraios, these elements congregate together or, if necessary, split apart, in order to achieve a resonance whereby painting speaks a language of its own. The Furies, he warns, are still with us. They have not gone away. It may be a different era then it was in the ancient times, but the Furies live on. Purposeful revenge is their mission. They are the vengeful guardians of those who have gone wrong today among those who have lost step with their humanity. This is the important message and essential aspect instilled in Nikos’s paintings. To become a painter on the level of Nikos Kypraios is more than a facile exercise. Insurmountable work is required. Such artists are forever testing the limits of what they know and what they feel they can do. Nikos is such an artist.

1 Robert Graves, Greek Gods and Heroes, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1960; p. 30.

Robert C. Morgan is a critic, writer, painter, art historian, and lecturer who lives and works in New York. In 1999, he was given the first Arcale award in international art criticism by the Municipality of Salamanca, and in 2011, was inducted into the European Academy of Sciences and Arts, Salzburg. Author of many books and literary hundreds of essays and monographs, he is currently Professor Emeritus in Art History at the Rochester Institute of Technology and conducts graduate seminars at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York.